“I thought I was healing like everyone else,” one mother shared “But weeks later, I still couldn’t control gas or stool. No one had told me why.”

Stories like hers are common. Women often leave hospital after childbirth with ongoing pain or leakage, unaware that they sustained a severe tear during delivery. Many later learn that what happened to them was not explained, recognised, or treated correctly.

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), about 3 in every 100 vaginal births in Australia involve a third- or fourth-degree perineal tear. These injuries can cause lasting physical and emotional effects.

Yet, despite these numbers, many women are never told what really happened — or that the problem may have been avoidable.

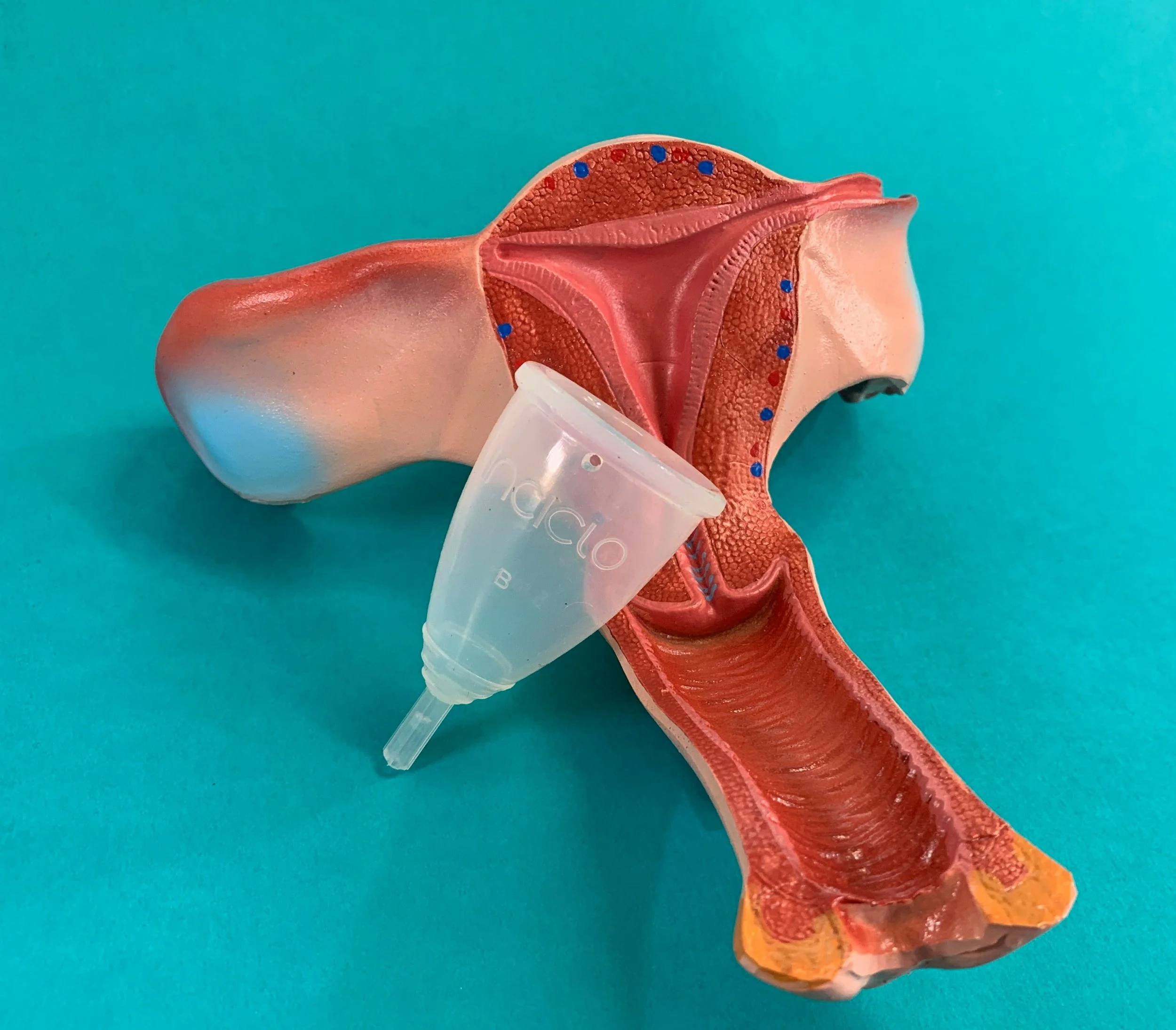

Understanding the Injury — Plainly Explained

A fourth-degree tear is one of the most serious birth injuries a woman can experience.

Here’s what it means in simple terms:

-

A third-degree tear goes through the muscle that helps control your bowel (the anal sphincter).

-

A fourth-degree tear goes even deeper, right into the lining of the rectum.

When this happens, the muscles that keep bowel contents in place are torn apart.

If not repaired properly, women can experience:

-

Pain that doesn’t go away

-

Incontinence (leaking stool or wind)

-

Pain with intimacy

-

Shame and embarrassment

-

Anxiety or trauma about the birth itself

These are not “normal” side effects of giving birth. They are signs of a serious injury.

A Gentle Start — You Are Not Alone

Many women leave hospital after giving birth believing everything went well—until weeks later, when pain, leaking, or embarrassment start to set in.

If you’ve found yourself Googling “why can’t I control my bowels after birth?” or “how long should an episiotomy take to heal?”, you are far from alone.

Every year in Australia, around 3 in 100 women who give birth vaginally experience a third- or fourth-degree tear, according to data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW, 2023).

Most tears heal well, but severe ones can cause long-term problems—especially if not recognised or treated correctly at the time.

A Realistic Birth Scenario

To understand how this can happen, imagine this:

Sarah is giving birth to her first baby at a public hospital in NSW.

The baby is large and lying slightly sideways (called “occiput posterior”). After hours of pushing, staff decide to use forceps to help deliver the baby. There is no detailed discussion of the risks.

During delivery, Sarah feels sharp pain — not just pressure. The baby is delivered safely, but she loses blood and is stitched quickly before being moved to recovery.

Weeks later, Sarah notices she can’t control gas and occasionally leaks stool. When she asks about it at her six-week check, she’s told this can happen after birth. Months later, a specialist finally tells her she had a fourth-degree tear that wasn’t properly repaired.

This is a typical scenario seen in maternity safety reports like the Ockenden Review (UK, 2022) and Australian obstetric case studies.

The issue is not that forceps were used — sometimes they are medically necessary — but that the risks weren’t explained, the injury wasn’t detected, and the repair was inadequate or rushed.

Each of those failures can cause long-term damage and may support a medical negligence claim.

Why Do These Injuries Happen?

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and AIHW list several risk factors:

-

First-time vaginal birth

-

Forceps or vacuum delivery

-

Large baby (>4 kg)

-

Long pushing stage

-

Episiotomy made in the wrong place or angle

-

Birth attended by inexperienced staff

From a legal standpoint, what matters is not that risk existed — but whether the care fell below accepted standards.

For example:

-

Was the perineum supported during delivery?

-

Was the tear recognised immediately?

-

Was repair done in a theatre by a qualified practitioner?

-

Was the woman told about her injury and given follow-up care?

If not, the injury may have been preventable.

What Is a Fourth-Degree Tear?

A third-degree tear goes through the muscle that helps you control bowel movements (the anal sphincter).

A fourth-degree tear goes even deeper—into the lining of the rectum.

Women who have this type of injury often describe:

-

Pain that doesn’t go away

-

Leaking stool or gas

-

Trouble sitting or returning to intimacy

-

Feeling dismissed when they raise concerns

These experiences are medically recognised symptoms, not personal failings.

How Do These Tears Happen?

Studies from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (UK, 2021) and the AIHW identify common risk factors:

-

A large baby

-

Forceps or vacuum delivery

-

Long or difficult labour

-

First-time vaginal birth

Good care includes:

-

Explaining risks before delivery

-

Supporting the perineum as the baby is born

-

Checking for tears afterwards

-

Repairing the injury in theatre by a skilled clinician

When these steps don’t occur, the risk of long-term injury rises.

Patient Safety and What Reports Show

Recent safety reviews overseas, such as the Ockenden Report (2022) in England, found repeated failures to recognise and repair tears properly.

In Australia, researchers writing in the Medical Journal of Australia (2021) have also raised concerns about gaps in maternity training and follow-up care.

These reports suggest a pattern:

➡ Staff shortages and rushed assessments can mean serious injuries are missed.

➡ Women are sometimes not told exactly what happened.

➡ Postnatal care for continence and pelvic-floor recovery is uneven across hospitals.

From a patient-safety viewpoint, these findings show how communication and staffing systems—not just individual clinicians—affect outcomes.

How to Know If You May Have a Claim

Not every injury will lead to a claim. Some severe tears occur despite reasonable care.

But a woman may have a medical negligence claim if:

-

The injury was not recognised or repaired correctly;

-

The hospital failed to provide proper follow-up;

-

Consent was not obtained for procedures like forceps or episiotomy;

-

Records or communication were inadequate;

-

She suffered ongoing loss because of those failures.

In NSW, the legal test asks whether the care was “below the standard of a competent professional” and whether that caused harm (Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW), s5O).

A lawyer can review your hospital records and seek an independent medical expert opinion. This process is confidential and does not mean you have to sue — it simply gives clarity.

When Might It Be Medical Negligence?

Not every severe tear is the result of negligence. Some occur even when everyone does their best.

But a claim may exist if:

-

The tear was not recognised or repaired correctly;

-

The woman was not told about the injury or how to manage it;

-

There was no referral for follow-up or physiotherapy; or

-

The care clearly fell below accepted professional standards.

In New South Wales, a medical-negligence claim generally requires proof that:

-

The provider breached the accepted standard of care; and

-

That breach caused the injury or made it worse.

An experienced lawyer can review hospital records and obtain an independent expert report to assess whether care met professional standards.

This process is about accountability, not blame—it helps improve safety for others.

Recovering Physically and Emotionally

Healing from a fourth-degree tear takes time. Helpful steps may include:

-

Specialist pelvic-floor physiotherapy

-

Review by a colorectal or continence specialist

-

Referral to a pelvic-floor clinic (available in many public hospitals)

-

Support from groups such as the Australasian Birth Trauma Association (ABTA)

-

Gentle counselling for trauma or relationship strain

Many women feel deep shame or anger before learning that what happened was preventable.

Validation often begins with understanding that you deserved proper care and honest communication.

How to Seek Answers Safely

If you think your injury was not handled properly:

-

Request your medical records—you have a right to them.

-

Write down your symptoms and when they began.

-

See your GP or a pelvic-floor specialist for assessment.

-

Get legal advice early—time limits apply to negligence claims in NSW.

Good legal advice should be calm, factual, and patient-centred.

A lawyer experienced in medical cases can explain your options without pressure.

Systemic Lessons

From a legal perspective, fourth-degree tears highlight the link between patient safety, training, and communication.

When hospitals invest in midwife education, structured risk assessment, and respectful aftercare, rates of severe tearing fall.

Legal cases—when brought carefully—can encourage those systemic improvements.

The goal is not litigation for its own sake, but safer births and informed consent for all women.

Final Words

If you are still in pain, leaking, or unsure what happened to your body, please know this:

It is not your fault. You have the right to care, answers, and support.

Understanding your legal rights is part of reclaiming your wellbeing.